"Gazing into Napoleon's eyes, Prince Andrei mused on the unimportance of greatness, the unimportance of life which no one could understand, and the still greater unimportance of death, the meaning of which no one alive could understand or explain"."

-Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

My Alternate Title:

War

and Russia or Why Napoleon Wasn’t all he Was Cracked up to

Be

I

don’t know if it’s a small strain of masochism, a wild desire for conversation

starters, a love of history and the classics, a past appreciation of Anna Karenina, or the wish to impress

the next Russian I meet, but I finally buckled down and read the novel whose

title is synonymous with length and boredom. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy.

|

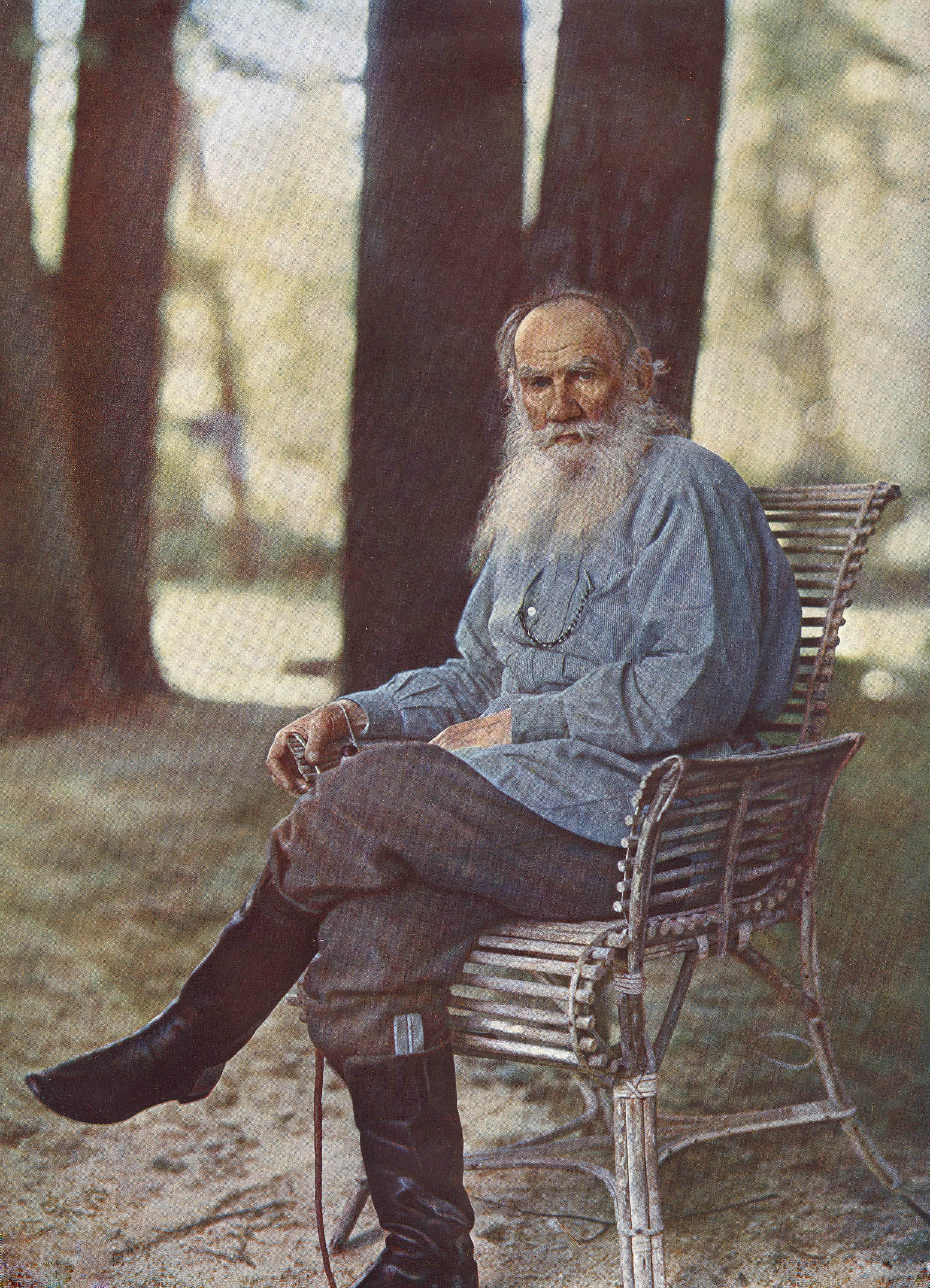

| Leo Tolstoy |

The

book is every bit as long as everyone says, coming in at #14 on the list of the

longest novels in Latin or Cyrillic alphabets with a word count of 560,000. It’s actually shorter than another

book I’ve read—twice—and enjoyed, Atlas

Shrugged, which is #11 with 645,000 words. W&P seemed much longer than Atlas,

though, partly because Mr. Tolstoy has a habit of getting on soapboxes and

chasing after rabbits. Perhaps he’s not as bad as Victor Hugo in Les Misérables (#17), but he does talk about history and battle

sequences constantly. And he included

two epilogues. Who does that?

Woven

throughout are dozens of weighty themes: unconditional love and forgiveness of

enemies, how marriages are painful and shallow when money is all that’s

concerned, the meaninglessness of “society life”, the dignity of mankind,

international policy, self-sacrifice, and longing for recognition, to name a

few. There’s also a fair amount of pure, abstract philosophizing (You find yourself

asking things like, “Is fire really an element or is it a phenomena?”). Loving,

dueling, gambling, fighting, rescuing, sacrificing, eloping—they all have their

place in W&P. You probably knew

this already, but don’t pick this one up if you’re looking for a light summer

read. Do pick it up if you’re looking for a thought-provoking, meaty classic

that sets a very high standard.

The Characters:

This

book follows the lives of fictional key characters—Pierre Bezukhov (an

ungainly, honest, naïve man), the Bolkonskys (an ambitious man and his

spiritual sister), the Rostovs (a close-knit aristocratic family), the Kuragins

(shallow, depraved, and manipulative)—as well as famous historical

names—Napoleon and Tsar Nicholas I. They all live in Russia at the turn of the

nineteenth century (during the time when Napoleon was trying to squash the

Russian empire into the snow), and all are influenced by and exert their

influence on the world, whether in social soirees, family gatherings, or bloody

battlefields. Some of them long for greatness, some for love, some for meaning;

these are universal desires that we can relate to.

This

book follows the lives of fictional key characters—Pierre Bezukhov (an

ungainly, honest, naïve man), the Bolkonskys (an ambitious man and his

spiritual sister), the Rostovs (a close-knit aristocratic family), the Kuragins

(shallow, depraved, and manipulative)—as well as famous historical

names—Napoleon and Tsar Nicholas I. They all live in Russia at the turn of the

nineteenth century (during the time when Napoleon was trying to squash the

Russian empire into the snow), and all are influenced by and exert their

influence on the world, whether in social soirees, family gatherings, or bloody

battlefields. Some of them long for greatness, some for love, some for meaning;

these are universal desires that we can relate to.

If

I had to find a single “main” character among the 580 in this novel, it would

be Pierre. Tolstoy actually wrote a bit of himself into the character, whose

primary goal is to find meaning in life. Not an easy task when you’re

surrounded by vapid convention, blatant immorality, hypocrisy, and carnage. He

tries marrying a gorgeous woman, attending social events, retreating into

religious mysticism, and striking out onto a battlefield, but only finds peace

while a prisoner of the French and the friend of a simple peasant man. Here he

learns that God is in control, He has a plan, and that is all that matters.

The Shallowness of

Society

Drawing

room chatter and fancy balls seem to have been the pinnacle of life to

thousands of aristocrats during this time in Europe. Tolstoy massacres their

pretty image with characters like Hélène and Anatol, who are really vicious

snakes deep inside, as he applauds women like Maria—pious and loyal to a fault.

The Senselessness and

Brutality of War

This

is a major theme. Tolstoy was actually

in an artillery regiment in the Crimean War and saw fighting firsthand. His

epic novel questions the transitory nature of war when society women in Russian

salons choose to speak in posh French, not long after the French stopped

blowing up their family and friends. The battle scenes are a bloody, smoky

chaotic mess with confused armies, corrupt officers, petty politicking and

meaningless action.

“Greatness”

Several

characters start out with a hero-worship of “great men” of their day: Napoleon

and Tsar Nicholas I. They have the same obsession with leaders that many of us

have (think Barack Obama, Ronald Reagan, or Jennifer Lopez). However, Leo beats it into the reader’s head that it is not the one or two leading figures

who are responsible for the outcome of world events, it is the “spirit of men”—even

little men—and the predestination of God that determines history. This

could be seen as a thesis concerning the creation of history. Over and over

again Tolstoy emphasizes that everything is “predestined from on high” and that

Napoleon wasn’t really a genius, he was just a pawn in the hands of God (and

not a very smart one at that). It takes the combined efforts of little guys

like Prince Andrei, Natasha Rostov, and Platon Krataev to make great things

happen. Hero worship falls away in the light of reality.

Conclusion

War and Peace has been described as one

of the greatest novels ever written. Leo Tolstoy didn’t even see his massive

work as a novel (he was a realist and considered a novel to be “a framework for

the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life”),

but an epic in prose. This is an epic

work, giving us a bird’s eye view as well as a microscopic analysis of love,

loss, and the meaning of life. We are all small things in the hands of a great

God. We are predestined to play our roles from eternity, and each one of us is

precious, though flawed. A recurring theme in the book is the sky as a symbol

for hope, a great reason for living—or dying—optimism, and love. It mirrors the

truth of life. I think that that is what Tolstoy would like to be remembered

for, rather than his ginormous word count.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for visiting! Please leave many comments, I love them!