The second part of my essay on sin, guilt, and hypocrisy in Nathaniel Hawthorne's writings...enjoy!

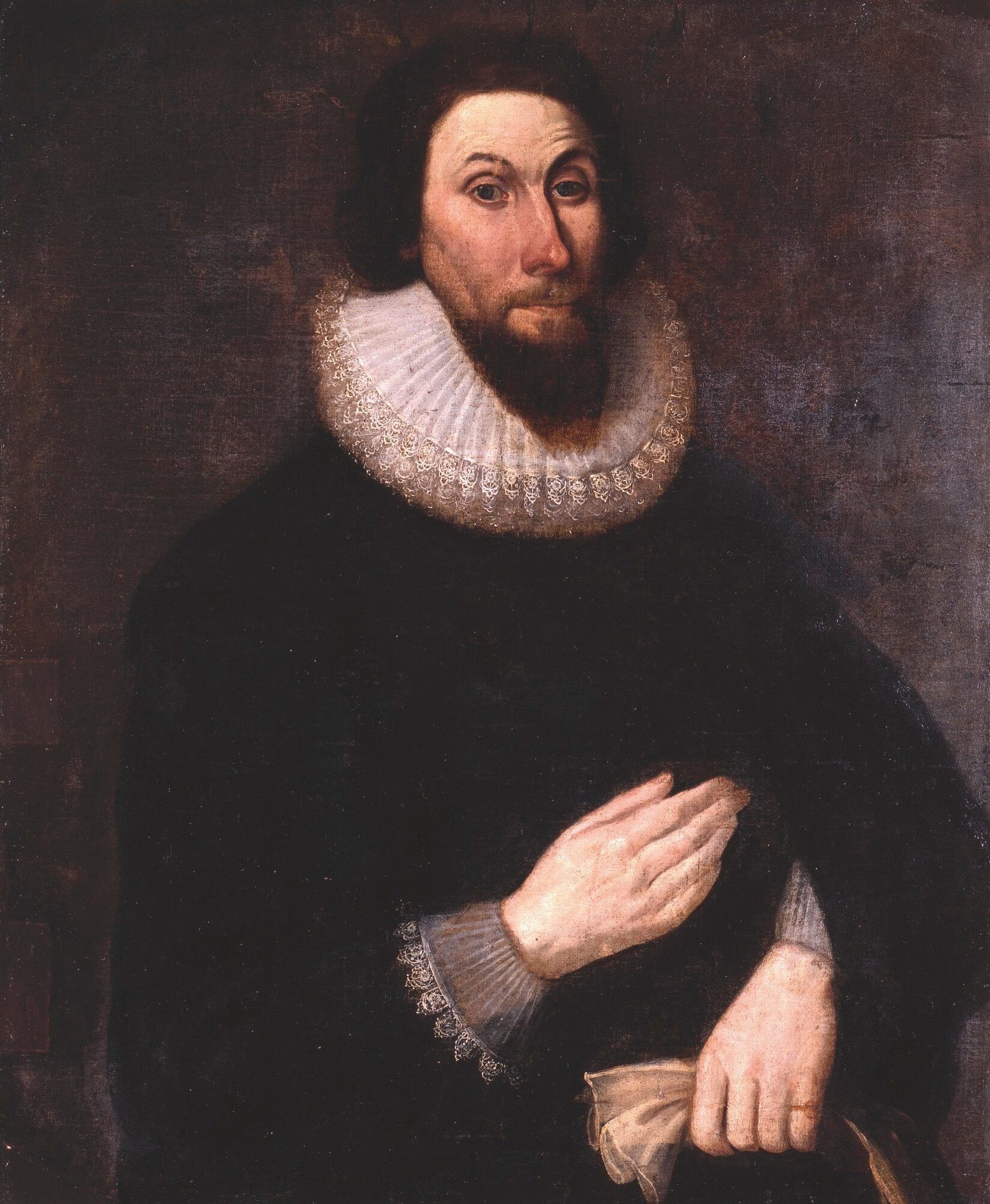

When reading Hawthorne’s work it is impossible to miss the influence of the Puritans’ perspective on sin; it permeates both the settings of his stories and their worldview. These early American Christians whom the author once described as “stern, severe,” and “intolerant” (Bloom Nathaniel Hawthorne 162) had a “comprehension of the evil in humanity (that) was second only to their condemnation of it” (Howard). Milk for Babes, a catechism written by prominent Puritan John Cotton, states that “Sin is the transgression of the Law,” “I was conceived in sin and born in iniquity….My corrupt nature is empty of Grace, bent unto sin, and onely unto sin, and that continually” (Cotton qtd. in Bloom, Young Goodman Brown 72). Ralph Venning, a 17th century minister, wrote a work titled Sin: The Plague of Plagues, in which he explained the pervading religious views of his times concerning evil and rebellion, “All God's works were good exceedingly, beautiful in admiration; but the works of sin are deformed and monstrous ugly, for it works disorder, confusion, and everything that is abominable” (32). Hawthorne’s most well-read texts all dwell upon the problem of sin, its nature and its penalties, and all of them reflect to a certain extent this Puritanical perspective.

Hawthorne’s personal attitude toward sin is hotly contested among literary scholars, but a few points are clear. Hawthorne faulted the Puritans for their brutal suppression of dissenters and sinners by his portrayal of Puritan characters in his writings. Many are shown as cruel, self-righteous hypocrites, as in his short story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount,” where they are “killjoys, at best, and ‘dismal wretches’ at worst” (Rogers 4). At the same time, Hawthorne was certainly influenced by the theology of his Puritan ancestors, and his fiction often goes into great detail concerning the darkness of sin within the soul, confirming the Puritanical doctrine of human depravity. In the introductory story to his novel The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne lets his readers eavesdrop on an imagined conversation between his Puritan forefathers, “‘What is he?...A writer of story books! What kind of business in life,—what mode of glorifying God, or being serviceable to mankind in his day and generation,—may that be? Why, the degenerate fellow might as well have been a fiddler!’

Such are the compliments bandied between my great grandsires and myself, across the gulf of time! And yet, let them scorn me as they will, strong traits of their nature have intertwined themselves with mine” (13). Those “intertwinings” have produced a body of literature that expresses a kind of “redeemed Puritanism” which emphasizes, not a Transcendental reliance on human goodness, but a belief in “original sin” and the necessity of confession and forgiveness.

Such are the compliments bandied between my great grandsires and myself, across the gulf of time! And yet, let them scorn me as they will, strong traits of their nature have intertwined themselves with mine” (13). Those “intertwinings” have produced a body of literature that expresses a kind of “redeemed Puritanism” which emphasizes, not a Transcendental reliance on human goodness, but a belief in “original sin” and the necessity of confession and forgiveness.

The Scarlet Letter, now considered to be Hawthorne’s greatest novel, is dominated by themes of guilt, innocence, hypocrisy, and absolution. The book begins with a fictional narrator (one who is clearly autobiographical) discovering an aged manuscript in the attic of a customs-house. That manuscript concerns one Hester Prynne, and the sordid history of her scarlet letter; the rest of the novel is a “retelling” of that story. Prynne is a beautiful, passionate, generous Englishwoman who married young and without love, then traveled to the New World while her husband remained behind in Europe to settle some affairs. When he does not arrive as expected, Prynne believes him to be lost at sea and allows herself to fall in love, ultimately committing adultery—a sin for which some Puritan lawmakers prescribed the death penalty—and bearing an illegitimate daughter. Hester Prynne is spared execution, but is sentenced to wear on her bosom a cloth letter bearing a scarlet “A,” so that all who should see her would know her sin. Though she takes her punishment with good grace, Prynne refuses to reveal the name of her child’s father, and he is a mystery for a good portion of the book. When his identity is eventually revealed, it is none other than the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale, a well-respected pastor with a stainless character and great clout in the community. While Hester Prynne must suffer her shame openly, bearing her infamy on her breast, Dimmesdale does not drink “the bitter, but wholesome cup” of confession, but “(adds) hypocrisy to sin” by keeping silence (62). If anything, his pain is worse than Prynne’s, for he is tortured in secret for years both by his own guilty conscience and by the reprehensible “Roger Chillingworth,” a man who pretends to be the reverend’s friend but is actually Hester Prynne’s revengeful husband living under an assumed name. The lives of these three people, and of Hester’s daughter, Pearl, weave together as the story progresses, until Dimmesdale is forced to confront his sin once and for all, and Chillingworth’s vengeance is spoiled.

The Puritan doctrine of original sin, sin which was passed on to the entire human race through Adam and separates every person from the perfect God, lies at the heart of The Scarlet Letter. Hawthorne’s characters, both sympathetic and despicable, suffer from the common human ailment of sin, in stark contrast to the Transcendentalist crowd which insisted on the goodness of human nature, with Ralph Waldo Emerson calling “the problems of original sin, origin of evil, (and) predestination…the soul’s mumps and measles and whooping coughs” (159). Hawthorne’s literary worlds mirror the world he saw around him, and what a reader sees reflected is sin lurking in all hearts—even the most unlikely ones. In his short story, “Young Goodman Brown,” Hawthorne describes a bizarre scene where Satan himself declares that his followers will be able to “scent out all the places—whether in church, bedchamber, street, field, or forest—where crime has been committed, and shall exult to behold the whole earth one stain of guilt, one mighty blood spot” (30-31). After Hester Prynne dons the shameful scarlet letter she finds that she has gained this strange power to sense sin even in those who appear to be righteous. Her lover, Arthur Dimmesdale, is in fact the last man in the world to be suspected of adultery, “He was a person of…a freshness, and fragrance, and dewy purity of thought, which, as many people said, affected them like the speech of an angel” (61). The Scarlet Letter shows readers a world where “if truth were everywhere to be shown, a scarlet letter would blaze forth on many a bosom besides Hester Prynne’s” (78).

Hawthorne’s major works illustrate three major responses to this problem of sin. The first response is to embrace sin, as Mistress Hibbins and Roger Chillingworth do in The Scarlet Letter. Mistress Hibbins, the sister of the honorable Governor Bellingham, is a self-professed witch who meets with Satan in the forest and rides a broomstick. Chillingworth’s acceptance of sin is more subtle; he allows his lust for revenge to overpower any forgiveness he might have extended to his adulterous wife and her lover, and he spends years of his life quietly chafing at Dimmesdale’s conscience. In chapter 13 Chillingworth speaks with Hester and declares his belief in the inevitability of sin, “Ye that have wronged me are not sinful, save in a kind of typical illusion; neither am I fiend-like, who have snatched a fiend’s office from his hands. It is our fate” (152). He is a rare example of the “unhumanised mortal” who rejects forgiveness in favor of evil (225). The more common responses to sin by Hawthorne’s characters are hypocrisy and guilt, both of which will be examined here in detail.

To be Continued...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for visiting! Please leave many comments, I love them!