Hawthorne’s personal attitude toward sin and sinners is somewhat ambiguous, despite the existence of a deliberately intrusive narrator in nearly every one of his tales. Some call this issue the “Hawthorne Question”; literary critics want to know what the author of such darkly tragic tales could have thought about the worlds he was creating, but Hawthorne remains a riddle. Did the author sympathize with Hester Prynne? Was his moralizing narration meant to be genuine, or derisively ironic? Was he a Puritan at heart, or did he in fact despise the Puritans? Views on his moral and aesthetic beliefs often contradict one another. One author writes that “many of the central tenets of Transcendentalism (awareness of the creative and imaginative power of nature, the breaking away from form and tradition, and the emphasis on individual experience) can be seen in stories like “Young Goodman Brown” and novels such as The Scarlet Letter” (Felton), while another says “transcendentalism as such touched him not at all” (Canby 231). Advocates of Traditional Historicism, a school of literary criticism that takes social contexts and authorial intent into consideration, would search for answers among Hawthorne’s personal letters, in the politics of his day, and in the friends he made. Supporters of New Criticism would be more likely to take an intrinsic approach and search only between the two covers of an individual tale.

|

| A scarlet letter, a photo by Monceau on Flickr. |

Despite his irreverent portrayal of the self-righteous goodwives, Hawthorne speaks of Hester Prynne’s “sin” (72), says, “She knew that her deed had been evil…” (80), and declares that she had been made strong, but learned much amiss (174). This gives the impression that though Prynne is an admirable woman compared to her countrywomen, she has committed terrible sins. Both views, Historicism and New Criticism, have their flaws in that neither is completely clear of an interpreter’s bias and limitations. The fact remains that despite our extensive knowledge of Hawthorne’s life and his own narratives’ constant commentary, the author remains ambiguous, as if silently asking his readers to determine the truth of his words for themselves. This is part of what so puzzles and fascinates those who look into the Hawthorne Question.

In relation to the totality of American literature, however, Hawthorne’s legacy is clear. He is best remembered for his works that illustrate original sin as a stain on the human race, which leads to guilt, with peace resulting from “being true.” This “popular” view tosses aside the idea that these tales were all written tongue-in-cheek by an optimistic Transcendentalist, and takes Hawthorne’s literature for what it declares itself to be—the writing of a “redeemed Puritan” who recognizes sin, and recognizes grace as well. This consciousness was a hallmark of the American Gothic tradition that Hawthorne brought out more than any of his contemporaries. His style, gloomy settings, tragic characters, and plots that delve into the dark side of the human spirit were elements which inspired some of his most celebrated contemporaries, most notably Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe.

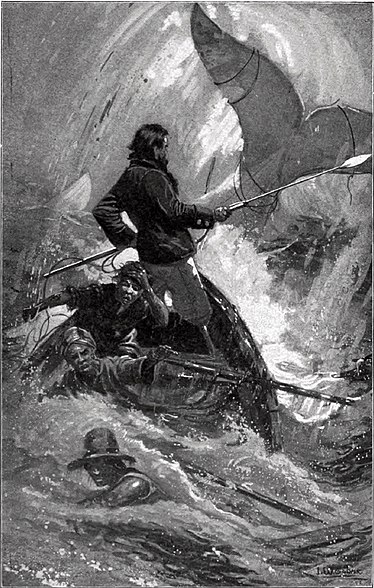

Hawthorne met Melville at a picnic in 1850, and the two men soon grew to know each other well. Hawthorne had just published The Scarlet Letter to great critical acclaim, and Melville imagined that he had found a creative genius as well as a soul mate. Hawthorne may have been responsible for encouraging Melville “to transform what originally seems to have been a light-hearted whaling adventure into the dramatic masterpiece that is arguably the greatest American novel of all time,” and Melville dedicated Moby-Dick to his inspiring friend (“Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne”). The themes of tragic revenge, skepticism of religious extremism, and questions of fate and free will in Melville’s novel are all strongly reminiscent of elements in Hawthorne’s work. Melville, the master of tragic humanity, acknowledged a literary debt to his friend when he wrote, “There is a certain tragic phase of humanity which, in our opinion, was never more powerfully embodied than by Hawthorne” (qtd. in Wright, 351).

Though he never met Hawthorne in person, Poe was a great admirer of his work. In a glowing review of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales, Poe writes, “we would say, emphatically, that they belong to the highest region of Art–an Art subservient to genius of a very lofty order” (334). Poe, a writer of short stories like Hawthorne, is probably the author whose style most closely relates to Hawthorne’s own. An avid anti-Transcendentalist, he agreed with Hawthorne about original sin and the impossibility of human perfection, and Hawthorne’s poetic, musical style may well have had a profound influence on Poe’s own work. Poe’s short story, “The Masque of the Red Death,” was written around the time he reviewed Twice Told Tales; the story is one of Poe’s first to make heavy use of Hawthorne’s style of enigmatic symbolism, as in the description of death as a masked man whose “vesture was dabbled in blood—and his broad brow, with all the features of the face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror” (Poe, 1588). Another Poe story, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” bears certain resemblances to “Young Goodman Brown”; both contain a strong theme of guilt and utilize foreshadowing, repetition, and symbolism.

Though he never met Hawthorne in person, Poe was a great admirer of his work. In a glowing review of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales, Poe writes, “we would say, emphatically, that they belong to the highest region of Art–an Art subservient to genius of a very lofty order” (334). Poe, a writer of short stories like Hawthorne, is probably the author whose style most closely relates to Hawthorne’s own. An avid anti-Transcendentalist, he agreed with Hawthorne about original sin and the impossibility of human perfection, and Hawthorne’s poetic, musical style may well have had a profound influence on Poe’s own work. Poe’s short story, “The Masque of the Red Death,” was written around the time he reviewed Twice Told Tales; the story is one of Poe’s first to make heavy use of Hawthorne’s style of enigmatic symbolism, as in the description of death as a masked man whose “vesture was dabbled in blood—and his broad brow, with all the features of the face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror” (Poe, 1588). Another Poe story, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” bears certain resemblances to “Young Goodman Brown”; both contain a strong theme of guilt and utilize foreshadowing, repetition, and symbolism.

Hawthorne’s literary influence did not end with the Gothic period. As one of the first American authors to delve into the past and tear away the veil of false optimism from religious hypocrites and starry-eyed philosophers alike, he initiated a literature of guilt, writings which reveal sin as well as its public and private effects. His self-conscious, semi-Puritanical emphasis on human imperfection “left a good many people uneasily or resentfully aware that possibly (the doctrine of sin) is true…. A lurking consciousness of sin has haunted American letters ever since (Kirk 255).

Hawthorne might not recognize his literary descendants today, as that “lurking consciousness” in 21st century writing has generally shifted its emphasis away from moral condemnation of sin toward a broader spirit of social reform, but the writers of “protest literature” are following in his footsteps. The tradition of protest literature in American writing has always opened up alternate points of view: on slavery, injustice towards American Indians, women's rights, the Great Depression, or controversial wars. While not a reformer himself, Hawthorne’s challenge to the optimists of his day opened America’s eyes to the reality of sin and the necessity for absolution, and paved the way for reformist writers who changed the world through the written word.

In his attempt to adhere to “the truth of the human heart” (Seven Gables 3), Hawthorne was a great inspiration to John Updike, an author who utilized similar narrative techniques and storytelling strategies. Updike was so impacted by The Scarlet Letter that he published three novels very loosely based on it during the 1970s and 80s. Updike has been described as “a modern Hawthorne,” who explored “the moral and psychological confusion of the community and its fraudulence and hypocrisy” (De Bellis 78). It could be argued that Updike took the core concepts of Hawthorne’s fiction and turned them on their heads, rejecting the division between the “corrupt material” and “pure spiritual” realities that give Hawthorne’s work so much of its impact, but the fact is that both authors addressed the same issues, the same human nature, the same search for truth and truth-telling (Royal 74).

In his attempt to adhere to “the truth of the human heart” (Seven Gables 3), Hawthorne was a great inspiration to John Updike, an author who utilized similar narrative techniques and storytelling strategies. Updike was so impacted by The Scarlet Letter that he published three novels very loosely based on it during the 1970s and 80s. Updike has been described as “a modern Hawthorne,” who explored “the moral and psychological confusion of the community and its fraudulence and hypocrisy” (De Bellis 78). It could be argued that Updike took the core concepts of Hawthorne’s fiction and turned them on their heads, rejecting the division between the “corrupt material” and “pure spiritual” realities that give Hawthorne’s work so much of its impact, but the fact is that both authors addressed the same issues, the same human nature, the same search for truth and truth-telling (Royal 74). |

| Arthur Miller's "The Crucible", a photo by thegreatgonzo on Flickr. |

Conclusion

When Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote those words, “Be true! Be true! Be true! Show freely to the world, if not your worst, yet some trait whereby the worst may be inferred” (Scarlet Letter 123), he urged his readers to own their humanity. He shows us that by recognizing the worst in ourselves and not being afraid to expose that to the world, we have the chance to find “real life” (127). His dark romanticism, far from being hopelessly pessimistic, speaks of a power that can transform our human infirmities into symbols of grace. Hawthorne did not shrink away from showing the worst of himself, his family history, or his country’s heritage, to his readers. One might say that writing about Salem and the Puritans was his own way of “being true,” exposing his own sinful nature and the wrongdoing of his forefathers while creating literary masterpieces that continue to inspire nearly a century and a half after his death. Hawthorne leaves his readers with this responsibility—it is imperative for each one of us to recognize and reveal the sin inside ourselves and in our world and eradicate guilt with nothing but the truth, though it be “the truth of red-hot iron” (80).

Works Cited

Bloom, Harold. Nathaniel Hawthorne. New York: Chelsea House, 2007. Print.

---. Nathaniel Hawthorne's Young Goodman Brown. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2005. Print.

Brown, Lurene. "Guilt in Literature." Thesis. Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, 1975. Print.

Canby, Henry Seidel. Classic Americans: A Study of Eminent American Writers from Irving to Whitman. New York, 1931

De Bellis, Jack. The John Updike Encyclopedia. Illustrated ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000.

Print.

Emerson, Ralph W. Essays and Lectures. Lawrence, Kansas: Digireads, 2009. Print.

Felton, Robert T. "Hawthorne and Transcendentalism." Lecture. The House of the Seven Gables

Annual Meeting. The House of the Seven Gables, Salem, Massachusetts. 4 Oct.

2006. Hawthorne in Salem. North Shore Community College. Web. 27 Apr. 2012.

Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. First ed. New York: Hill and Wang,

2007. Print.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. Grandfather's Chair: And Biographical Stories. Boston: Houghton,

Mifflin &, 1896. Print.

---. The House of the Seven Gables. Rockville, MD: Arc Manor, 2008. Print.

---. The Scarlet Letter. Revised ed. New York, NY: Penguin, 2002. Print.

---. Young Goodman Brown. Rockville, MD: Wildside, 2005. Print.

Howard, Melissa. "Good & Evil in Young Goodman Brown." Suite101.com. Melissa Howard, 16

Jan. 2009. Web. 05 Apr. 2012.

goodman-brown-a90492>.

Kirk, Russell. The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Pub.,

2001. Print.

"Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne." The Life and Works of Herman Melville. n.d. Web. 27 Apr.

2012. .

Morrison, Dane A., and Nancy L. Schultz. Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory. Illustrated ed.

Boston: UPNE, 2005. Print.

Poe, Edgar A. "The Masque of the Red Death." 1842. The Norton Anthology of American

Literature. Seventh ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007. 1585-589. Print.

Rogers, Abigail. Personal Journal. 6 Apr. 2012.

Royal, Derek P. "An Absent Presence: The Rewriting of Hawthorne's Narratology in John

Updike's S." Critique 44.1 (2002): 73-84. Rothsociety.academia.edu. Web. 27 Apr. 2012.

Sutcliffe, Katherine. "Sarah Good." Famous American Trials. UMKC School of Law, n.d. Web.

27 Apr. 2012. .

Trepanier, Lee. "The Need for Renewal: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Conservatism." Modern AgeFall

2003: 315-23. Http://home.isi.org/. Intercollegiate Studies Institute. Web. 5 Apr. 2012.

Venning, Ralph. The Sinfulness of Sin. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1993. Print.

Wright, Sarah B. Nathaniel Hawthorne. New York: Infobase, 2007. Print. Critical Companion

(Facts on File Library of American Literature).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for visiting! Please leave many comments, I love them!